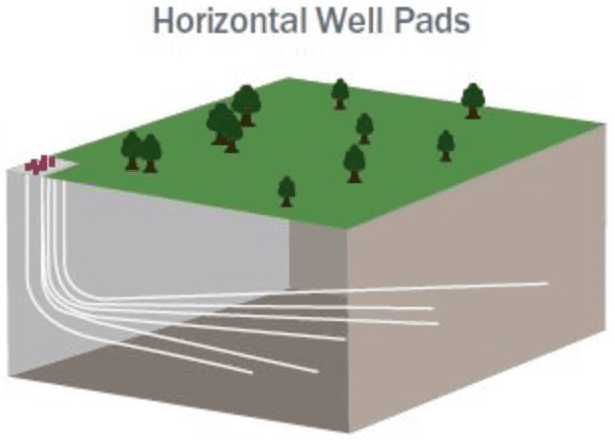

Wellsite Facilities and Multi-Well Pads

An upstream horizontal multiwell pad is a single surface site where an operator drills and completes multiple mostly-horizontal wells into one or more subsurface reservoirs, then ties them into shared production infrastructure. This development style is common in unconventional plays because it increases reservoir contact while reducing surface footprint and per‑well costs.

- Greenfield, Brownfield or MOC (Management of Change) Projects

- Single Well pads

- Multiwell Pads

- Mega Pads

- Wellsite scada

What is an upstream horizontal multiwell pad?

In upstream operations, a pad is a prepared surface lease (often gravel) that hosts the drilling rig, wellheads, and associated equipment. On a horizontal multiwell pad, the rig drills several wells from that same pad, typically starting vertically, building angle, and then landing a long horizontal lateral in the target zone. Laterals often diverge like spokes from the pad location, allowing access to a broad drainage area from one surface site.

Unconventional oil and gas developments in shale and tight formations rely heavily on this concept because one horizontal well with multiple frac stages can match or exceed the productivity of numerous vertical wells. Multiwell pads may host anywhere from three to ten wells or more, depending on spacing, geology, and economics. The pad also typically includes shared facilities such as separators, tanks, flare, and sometimes water handling and gas lift or compression equipment.

Key advantages

-

Reduced surface footprint and land impact

Multiwell pads allow producers to contact a large underground area from a relatively small surface site, meaning fewer leases, access roads, and clearings compared with single‑well development. Studies have shown that developing the same resource with single‑well pads would disturb roughly two to four times more land than using multiwell pads. -

Higher drilling and completion efficiency

Keeping the rig and completion spreads on one pad for multiple wells enables batch drilling and streamlined logistics, reducing rig move time and associated costs. Operators can drill groups of similar hole sections, then skid or walk the rig a short distance between well slots instead of fully rigging down and hauling offsite. Concentrated activity also simplifies scheduling of frac crews, wireline, and other services, driving down per‑well time and cost. -

Shared infrastructure and lower unit costs

Pad technology allows containment, roads, utilities, and production equipment to be amortized across multiple wells rather than duplicated at many small sites. This reduces capital per flowing barrel or per Mcf since fewer separators, tank batteries, flares, and pipelines are required per well. Concentrated infrastructure also tends to lower transportation costs for materials, fuel, and personnel. -

Improved environmental performance per unit of production

Because multiwell pads minimize the number of distinct sites, they typically reduce total disturbance, road miles, and edge habitat fragmentation for a given level of production. Analyses of unconventional gas operations show that multiwell pads often have fewer environmental violations per well and higher onsite water recycling rates than single‑well pads. -

Operational flexibility in development planning

From a reservoir management perspective, multiwell pads support systematic development: wells can be spaced and oriented to maximize contact and manage interference. Operators can stage drilling and completion sequencing (e.g., zipper fracs) across wells on the pad to optimize productivity and cycle time.

Key disadvantages

-

Delayed cash flow from first wells

One drawback is the lag between spudding the first well and bringing the pad on production, because operators often wait until most or all wells on the pad are drilled and completed before turning the pad over to operations. Each additional well on the pad extends the “spud‑to‑sales” timeline, slowing early cash flow even though total pad returns may improve. -

Higher upfront capital and complexity

Multiwell pads concentrate capital into fewer, larger projects: drilling several horizontals, full frac programs, and shared facilities at one time. This higher upfront spend can strain budgets and requires more rigorous planning of supply chains, water management, frac sand, and takeaway capacity. If commodity prices deteriorate mid‑program, sunk costs are larger than for a series of small single‑well sites. -

Well interference and spacing challenges

Placing many horizontals from one pad increases the risk of wellbore collision during drilling and production interference or frac hits during completions if spacing is not optimized. Finding the “sweet spot” in terms of number of wells per pad and inter‑well spacing is non‑trivial, as crowding wells can flatten efficiency gains and hurt productivity. Monitoring offset pressure, microseismic, and production is needed to manage these risks. -

Concentrated operational and safety risk

Having multiple wells and high‑intensity frac operations on a single pad increases the consequences of operational upsets, including well control incidents or equipment failures. Emergency response planning for multiwell pads must account for simultaneous operations (SIMOPS), more complex evacuation and shut‑in scenarios, and greater onsite inventories of fluids and proppant. -

Community and traffic impacts during peak activity

While long‑term disturbance per unit production is lower, short‑term activity at a multiwell pad can be intense, with continuous truck traffic, noise, and light during drilling and completions. This concentration of activity can raise community concerns even if the overall number of pads and roads is reduced.

Overall assessment

For modern unconventional upstream projects, horizontal multiwell pads are typically the preferred development model because they align strong economic efficiencies with reduced surface impact at the field scale. However, these benefits depend on careful pad design, well spacing, operational planning, and risk management to avoid delays in cash flow, interference issues, and concentrated safety or community impacts.